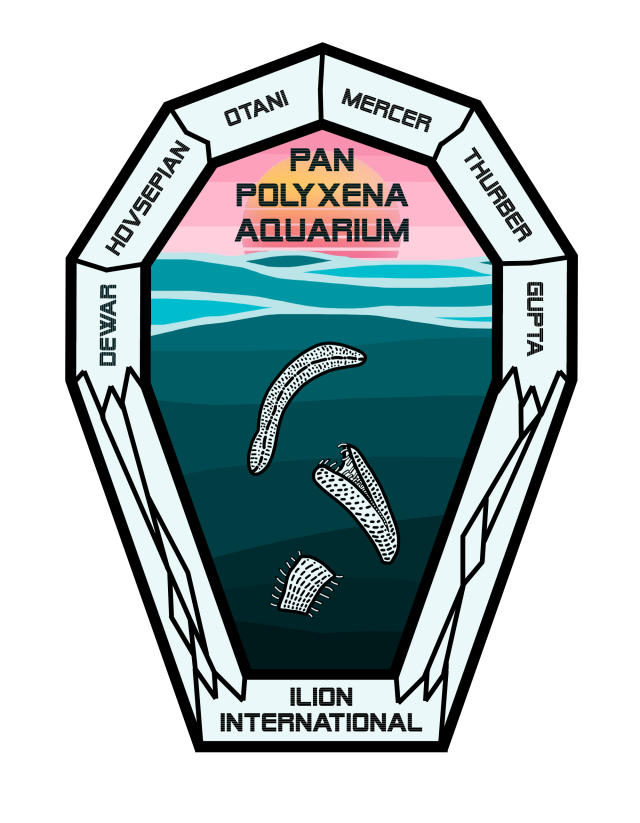

Led by a small team of scientists including two members of Odyssey II, this Earth-based facility maintained cultures of alien life collected by Odyssey crews, mostly sea life off the coast of Polyxena.

Cryopreserved seawater concentrates were first thawed out in a secret facility in Australia, which stationed Ilion International’s top scientists. Reviving the lifeforms housed in the concentrates was challenging enough. A revival protocol was supposed to be developed on board Odyssey, but the laboratory was tied up with more urgent projects.

It took half a year and roughly a tenth of the samples to achieve an acceptable success rate – 85%. They would find out much later that this was about as high as it could possibly go. The reason? Embryos and algae dredged from the waters around Polyxena were naturally tolerant of freeze and thaw cycles. Anywhere else, and the resident life would have a much harder time surviving the process. A percentage of those collected were drifters from temperate waters, doomed to perish or be consumed.

And so the team met its second challenge. Most of the samples yielded two kinds of life. First was the algae, easy enough to culture with the right kind of light and nutrients, studied carefully in situ and replicated here on Earth. The other lifeform was far more puzzling. Millions of nearly identical tubes, only a few cells thick, writhed out of cryo into the hands of a species that had no idea how to raise them. Raise them, for these were larvae, with the potential to develop into any number of species.

Plicozoans, they called them. Folding animals. They began their lives as sheets of cells, which would then fold into a tube with most of their organs developing along the seam. It was an elegant way to make a worm, but not all of them were content to remain worms. To grow into a fish, or an archersnake, specific conditions had to be met. Therein lied the challenge. Once the scientists set the parameters to grow a swordsquid, for example, most other larvae in that batch would be left in the lurch. The only way to grow an ecosystem’s worth of species without losing most of them was to create an ecosystem in miniature.

There was not enough variety in the algal colonies to build an ecosystem. A soil scientist named Tieran Thurber, one of the founding members of the facility, proposed a controversial solution. Why not tap into the diversity of Earth’s biosphere to create a perfectly balanced habitat for plicozoans? The hardest part, it turned out, would not be developing a hybrid ecosystem, though it was still an ambitious undertaking. The hardest part would be convincing his colleagues that this was a good idea.

Staffed 24/7, monitored and tweaked constantly by ecologists and biologists, the Pan-Polyxena Aquarium became the center of a whole host of novel fields of research. Xenogenetics, xenobiochemistry, xenobehavior, and heck, even xenopathology were on the menu for Earth’s scientists. While not open to the public, the PPA fed into the world’s consciousness through media and a robust outreach program.

EXCERPT The Other Red Planet: A history of the Odyssey program Raya Andiyar

The car dropped us off at an aging business park by the docks. A dozen or so gray and blue wings, each emblazened with a generically sciencey logo, surrounded a grassy courtyard that may have once been a parking lot.

“So which one is it? ‘Genzen?’ ‘Allodigm?’ What does that even mean?”

“It’s none of them. We couldn’t bring the car too close. The location’s a secret. Even you aren’t supposed to see it, but what do they expect me to do, blindfold you?”

We passed Genzen and rounded a corner. Another business park. Nemo flashed his ID at the gate, then guided us through a door that opened to the booth itself, where a guard would have sat had it been manned. The whole thing was fake. The real security checkpoint could be found down a ladder in the booth’s floor. It was like something from an old spy movie.

Gowning in was a complicated procedure. First, we showered, then changed into sterilized inner garments. They were airy and soft, designed for comfort and sweat management. And, yes, we wore diapers too. Afterward, we walked through an air shower which removed dust and dried our hair off somewhat. Finally, we stepped into positive pressure suits, hooked our air hoses to ports in the ceiling, and stepped into the fogger for our final sterilization. The process took about thirty minutes.

As we walked through the lab, we had to pull our air hoses with us. They slid along the ceiling on runners and it was too easy to forget them when walking past benches, hoods, tanks, and doorways. Mine would catch on something every few steps, while Nemo managed his without effort. I was relieved when he sat us down at a biosafety cabinet to begin his work.

“This one’s going to be a volcanoid,” Nemo would mumble as he sorted plicozoans under a dissecting scope. Unable to use an eyepiece in his suit, he would blow his work up on a screen mounted to the back of the hood. His hands would make the smallest movements seemingly without his attention, like they were being controlled by someone else. He was manipulating the organisms with a paintbrush trimmed down to a single hair. A worm would glide offscreen and the next would appear in one fluid motion.

I asked him how he knew what the worm would turn into. “The seam is puckering out,” he explained, “It will become like a teardrop within a couple days. Only volcanoids do that.”

He refused to call the seam by its commonly accepted name, Hovsepian’s line, or the H-line. The H-line was a universal feature of plicozoan development. The organisms would begin as a sheet of cells which folded into a tube, and most differentiation would occur on the resulting seam. I asked him why he wouldn’t use the term.

“They can name things after me when I’m dead. It’s against my religion to name children after the living,” he said, only half joking.

“You consider the plicozoans your children?”

He didn’t answer.

Later, he brought me to the seawater sample banks. He carried a container of liquid nitrogen he called a Dewar flask – “no relation to my colleague,” he said – which held the vials of plicozoans he had so painstakingly sorted earlier. Organizing them by species, or something close to it, would boost their survival rate significantly. It was enough to offset the losses caused by the extra thaw and refreeze cycle. By the time of my tour, an estimated 400 unique organisms had been lost.

“Does it sadden you when a species doesn’t make it?”

“Well, first, there’s always hope that it can still be found in one of our remaining samples. But the more we thaw out, the less likely that is. So yes, I do mourn them. But their kind are not truly dead. They are simply at home. Maybe we’ll come back for them one day.”